Susannah Heschel Discusses Her Father, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Martin Luther King & Selma

Ari Folman Stays Animated For Hollywood Satire

By Stephen Applebaum

Six years ago, Israeli film-maker Ari Folman found himself travelling the world on promotional duties for Waltz with Bashir. The movie was an animated, highly personal account of his search for lost memories of his time as a 19-year-old soldier in the 1982 Lebanon war, particularly during the notorious massacre of Palestinians by the Christian Phalangist militia at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut. The film garnered international acclaim, winning a Golden Globe and making Oscar history by becoming the first animated feature to be nominated for the best foreign-language film award. It should have been a happy time. However, the director — whose extraordinary new film The Congress opens in the UK this week — paints a darker picture.

“For me, travelling for nearly a year, talking about the war and myself became a nightmare,” recalls Folman, speaking from his home in a village 25 kilometres north of Tel Aviv. Waltz with Bashir had been a film “that I had to do”. But, after it, “I wanted to do something completely opposite. And I thought that sci-fi could give the perfect escape route, and it did in many ways. The Congress was me running away from Waltz with Bashir.”

Yet the Gaza conflict cannot help but remind him of the past. Although the sirens near his home have remained silent so far, in Jaffa, where his studio is based, they have gone off “once or twice a day on average. We were supposed to go to the safe room [when the sirens went off], which, basically, is the staircase of the building.

That is more [the situation] on a practical level. I would say that more than anything for me, it’s depressing.” Because it feels like history repeating itself? “Because it keeps happening again and again and again. This is very sad. And the fact that there is no horizon, that there is nothing to look forward to in the future, is even worse.”

Folman admits that he has become “less and less optimistic” about a solution to the conflict being found. “I think there are no leaders that can take tough decisions from both sides and make compromises,” he says grimly.

Waltz with Bashir split opinion when it was released in Israel. “There were people who thought I had betrayed my country,” he recently told an Irish newspaper. “I was a collaborator. But a lot of people thought I was doing something that was opening young minds.”

Would the reaction be different today? “That’s a clever question,” he responds drily. “It would be a nightmare to release the movie now. And a dangerous thing as well. Physically dangerous. That is because public opinion changed and became more radical.”

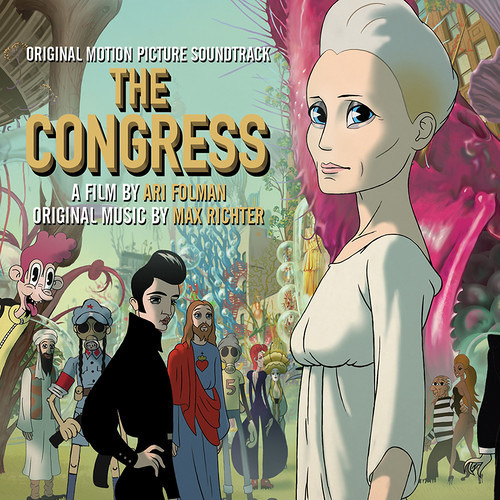

He is on safer ground with The Congress — adapted from Stanislaw Lem’s novel, The Futurological Congress — a blistering mix of live action and animation that is part mind-bending sci-fi, part coruscating Hollywood satire and part meditation on consciousness, identity and being human.

At its core is a compelling, multi-layered performance by Robin Wright, playing a version of herself who, when told that her career is over, signs a contract allowing a studio to use her digital likeness in new projects while she goes off and lives her life elsewhere. It sounds simple, but technological developments and the studio’s increasingly outrageous demands take Wright, the film and the viewer on a wild, surreal head-trip that will baffle some and enthral others.

Ironically, The Congress feels angrier than Waltz with Bashir, although Folman takes a different view. “The reason I went to film school was because the role of a director was mainly to make magic happen on the set in a very limited period of time, between yourself and the actors, the cinematographer, the art department. And if it was not created on the set, nothing would save you. Today, the set is just a platform for making the movie in post-production, in many cases. So I wouldn’t use the word ‘anger’. I would use the word ‘longing’ — for a different era in film-making.”

He believes we are seeing the end of the cinema-going experience as we know it, predicting that, in five years’ time, going to watch a movie will be like going to a concert. “Maybe the next Mike Leigh movie — well, the one after that — will be screened in a museum, not in a multiplex,” he muses.

Folman hopes that his next venture, an animated version of the Anne Frank story, will be seen by as many people as possible.

His parents met in the Lodz ghetto and were married on August 18, 1944. The following morning they were sent to Auschwitz. He had no intention of doing another animated feature, or making a Holocaust film. But when approached to tell Anne’s story, he quickly realised that he had to do it. He is being given access to the Anne Frank archives.

“They want me to make it for young teenagers. For me it was an offer I could not refuse, considering that both my parents are Auschwitz graduates. I see it as a great mission for me.”

With renewed antisemitism around the world and the day nearing when there will be no more survivors to bear witness to the Holocaust, Folman agrees that it is imperative to find fresh ways of keeping the memories alive for future generations. “When I see my kids performing on Holocaust Day in their school, I am embarrassed to sit in the audience,” he says. “They’re quoting things we quoted 40 years ago and they don’t understand anything in any depth. Nothing. So we do need to find the right way to keep on telling these stories, definitely.

“At least you give the Jewish people an option to memorise and understand what it means."