Jonathan

Holiff wanted to forget his father, Saul, after he committed

“rational suicide” in 2005. They'd been estranged for decades,

and Jonathan only had painful memories of the hard-drinking man whose

coldness blighted his youth. He'd left Canada, aged 17, determined to

earn his showbiz father's respect by bettering him professionally.

Despite doing well in Hollywood, none came.

“[My]

entire adult life had been a knee-jerk adolescent reaction to my

father's lack of approval,” Holiff says down the line during a

visit to Los Angeles. “So I realised, after his death, that I was

truly unhappy, and no longer had an interest in the superficial

existence that I had pursued and embraced as a consequence.”

He

sold his business in Tinseltown and drove back to Canada, thinking

he'd also left Saul behind. However, as revealed in his compelling

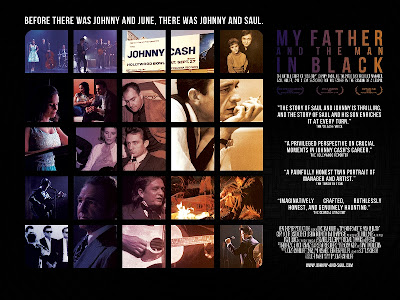

documentary, My

Father and the Man in Black,

Holiff was in fact beginning a journey that would force him to

re-think his father.

Looming

over their story is Johnny Cash, the Southern Baptist superstar Saul

- a Jew “as serious as a heart attack”, according to band mates -

managed for 13 years, before mysteriously quitting at the height of

Cash's fame. When journalists and biographers started calling with

questions about Saul and Johnny's relationship that Holiff couldn't

answer, his mother remembered that after retiring, her husband had

put his business things into a storage locker.

“I

was unable to bring myself to open the door because I didn't want to

wade into my father's life,” says Holiff. “I was still un-evolved

emotionally. I was still practising denial.”

Two

months after his return, Walk

the Line,

starring Joaquin Phoenix as Cash and Reese Witherspoon as June

Carter, his singing partner and second wife, opened, and people

wanted to know what Holiff thought of the glossy biopic. “It seemed

almost as if I was being punished at first, and certainly seemed like

a conspiracy of some kind,” he recalls wryly. Nevertheless, he

reluctantly went along to the cinema, and although Saul was erased

from the film's “whitewashed” storyline, it was eye-opening.

“I

was so unfamiliar with the specifics of my father's career that not

only did I not know that it was Saul who hired June and put her with

Johnny professionally, I hadn't realised that Johnny was famously

arrested [on drug smuggling charges in El Paso] the year I was born.

When I saw that I failed to really watch the rest of the movie,

because it opened a floodgate of repressed or forgotten memories of

childhood.”

Holiff

decided to face the storage locker. “I wanted to find out if there

was anything about his children among his most important documents

and archives. And the answer was, no.”

What

he did find was life changing. Among Saul's belongings – which

included a gold record awarded to him personally for a million-plus

sales of A

Boy Named Sue

– were more than 60 hours' worth of intimate audio-diaries and

recorded telephone conversations between Saul and Johnny. As a child,

Holiff knew Cash as a “very special and kind and generous” man.

Now he discovered a young, pill-popping rebel nicknamed Johnny

“No-Show” Cash whom Saul struggled to manage. (He missed an

entire tour just before Holiff was born, leaving Saul – as he so

often would - to pick up the pieces, and worrying about money.) The

filmmaker also learned that when he was nine months old, he was on

the road with Cash in Toronto, in 1966, when the singer “overdosed

and nearly died, and we all drove to Rochester across the border,

risking arrest for the discovery of pills [hidden somewhere] in the

motor-home.”

Holiff

had never understood before why Saul had treated him and his brother

like clients, including making them sign contracts, while they were

growing up. “I realised that

[Saul] was dealing with a very volatile character in Johnny Cash . .

. who was very much like a wild child, and he perhaps [tried] to

control us from the beginning and mould us into what he expected from

his children.” Holiff rebelled, though, “much like Johnny Cash

did, only not quite as famously and spectacularly.”

Walk the Line suggested that Cash gave up drugs - he didn't. The film also failed to address his becoming Born Again.

Jonathan

always wondered why his father had flown into a rage when he came

home from school, aged eight, and declared that he wanted to be known

as John. “He absolutely blew up, and I thought he was going to

physically kill me and take me apart. He said, 'Your name is not

John, it's Jonathan. John is a Christian name and you shall not use

it.'” Going through Saul's files, he realised that this was around

the same time that another John – Johnny was Cash's stage name -

was trying to convert his father to Christianity.

In

a recording about his childhood, his father says he grew up

surrounded by almost “palpable anti-Semitism.” Nonetheless, he

remained proud of and open about his Jewish identity. One of Holiff's

more surprising finds, therefore, was a photograph of Saul as

Caiaphas – the Jewish High Priest supposedly involved in the plot

against Jesus – in Cash's self-funded film shot in Israel about the

life of Christ, The

Gospel Road.

Saul had never discussed it afterwards, not even with his wife.

“The conclusion we drew was that he quickly regretted having done it and it was a source of pain for him for many years,” says Holiff. In one of the actual excerpts from Saul's audio-diaries used in the film, he asserts of Cash: “He robbed me of my soul and now I think he's trying to save it for me with his fundamentalist Christianity jazz.” Not long after, he resigned.

“I

think he woke up and realised just how far he'd gone without perhaps

even realising what he was doing,” Holiff suggests. “So I think

that's the straw that broke the camel's back in their relationship.”

Listening

to Saul's self-lacerating and self-aware recordings, his expressions

of guilt over not being a better father, and disclosures about his

own troubled upbringing, Holiff came to see Saul as a

three-dimensional human being for the first time. Has he forgiven

him?

“Here

is a guy who was wealthy, successful, had stature, was working with

the biggest-selling recording artist in the world in 1970 - Johnny

exceeded The Beatles' sales in the United States, briefly, in 1969 -

and he never found happiness. So I was very forgiving of him.”

Copyright Stephen Applebaum, 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please be civil